Doubt – critical power or heresy?

Introduction

In the “Religion and Childhood Trauma” series, we have previously explored how deeply religious beliefs and practices affect children’s early development and psychological well-being. So far, it has been about:

Doubt can be understood as uncertainty or lack of conviction about a statement or situation. It involves questioning the truth or validity of something. Doubt is a fundamental aspect of human consciousness and thinking linked to the human ability to transcend boundaries. There is an inescapable uncertainty inherent in human existence. That is the source of the enduring nature of doubt in history.

Doubt encourages questioning beliefs, seeking evidence for claims, and recognising the possibility of being wrong. This process of questioning and uncertainty encourages an open-minded approach to knowledge and enables continuous learning and growth.

Bertrand Russell calls doubt a necessary intellectual attitude when dealing with religious beliefs and dogmas. He criticises the suppression of doubt in favour of blind faith and points out the dangers that arise when the truth is ignored in favour of upholding social norms. He encourages scepticism and critical thinking when approaching religious and philosophical questions.

1. Doubt and certainty

Once Zhuang Zhou dreamed, he was a butterfly, a fluttering butterfly. What fun he had, doing as he pleased! He did not know he was Zhou. Suddenly, he woke up and found himself to be Zhou. He did not know whether Zhou had dreamed he was a butterfly or if a butterfly had dreamed he was Zhou. Between Zhou and the butterfly, there must be some distinction. That is what is meant by the transformation of things.

This Daoist parable from 4th century BC China emphasises that, ultimately, we cannot be sure whether Zhuang Zhou is perhaps a butterfly after all. That immediately raises the question of when a statement can adequately describe reality. Doubt is essential for distinguishing between dream and reality. It causes us to question certainties and prevents us from unquestioningly accepting perceptions of reality.

2. Doubt and curiosity

Doubt is part of the process of thinking. In this sense, thinking must be self-destructive because it constantly re-evaluates and questions previously gained knowledge. Doubt drives the pursuit of knowledge and understanding.

3. Doubt and human existence

The ability of the human mind to doubt the reality of its existence, as described above, is also a result of thinking. While thinking can quickly grasp various aspects of reality, the truthfulness of one’s existence remains elusive.

4 Doubt and faith

Doubt is a counterweight to unquestioned faith, especially in dogmatic religious contexts. Suppression of doubt in religious contexts leads to blind obedience and dogmatism.

1 Hannah Arendt and The Life of the Mind

In various philosophical traditions and cultural beliefs, doubt is not only seen as uncertainty or disbelief but as an essential tool for deeper understanding and spiritual growth. It challenges the individual to think critically, question constantly, and arrive at a more profound, personal conviction.

In “The Life of the Mind”, Hannah Arendt presents doubt as a complex phenomenon that calls into question the certainty of one’s consciousness. Blaise Pascal resisted René Descartes’ idea: “I think, therefore, I am” because it simply makes self-consciousness the guarantee of all certainty. On the other hand, Pascal emphasised the possibility of doubt to undermine even the most basic assumptions about reality.

She, therefore, also examines the role of doubt in religious belief and emphasises the importance of acquired faith and the limits of reason in proving or disproving religious truths. There is a gap between knowledge and opinion that cannot simply be bridged by argument. Practice is based on opinions and beliefs, which are not necessarily truthful despite their successful applicability.

In ancient times, for example, the Mediterranean was the heart of seafaring and facilitated exchange between the civilisations of the Middle East, North Africa, and Europe. Important sea routes connected Egypt, Greece, the Roman Empire, and the Phoenicians. The Black Sea allowed Greek and later Roman traders access to Scythia. Goods could be transported to India and back via the port of Alexandria and other harbours on the Red Sea coast. Although less well documented, there is evidence that the Phoenicians, and possibly other ancient seafarers, sailed along the shores of Europe and as far as West Africa. In addition, routes across the Indian Ocean connected the Red Sea and the east coast of Africa with the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia. These routes were also highly successful in spreading cultures, languages, and technological innovations.

This practice contrasted with various theoretical ideas about the Earth’s shape in antiquity. In many early cultures, it was assumed that the Earth was a disc floating on or surrounded by oceans, for example, among the Mesopotamians and Egyptians, as well as in some early Greek sources. It was not until the 6th century BC that some Greek philosophers, such as Pythagoras and later Plato and Aristotle, began to advocate the idea that the Earth was spherical. Nevertheless, Aristotle and subsequent scholars such as Ptolemy were firmly convinced that the Earth must be at the centre of the universe. According to him, celestial bodies (stars, planets, the sun and the moon) should be bound to transparent, fixed spheres that revolve around the Earth. Each heavenly body would have its own sphere. The fixed stars would be located on the outermost sphere and would revolve around the Earth as a whole. This sphere rotates once a day on its axis, which explains the daily rising and setting of the stars.

Doubt reveals the unavoidable limits of opinions and the subjective nature of practical thinking, as well as the fact that certainty and objective truth cannot be achieved simultaneously. Doubt, therefore, requires judgement. However, judgment, as the highest intellectual activity, does not produce actual knowledge. Such a claim to knowledge of the truth of judgment would be misleading. Political judgement, for example, cannot simply be equated with political knowledge or wisdom. Arendt emphasises that in doubt, human judgement creates meaning and anchors people in a world that otherwise cannot have any human meaning at all. Judgements answer questions of doubt that cannot be solved by knowledge or practical will alone. Judgement is, therefore, the central element in human thought and will to address existential questions and find solutions to hopeless situations.

When in doubt, judgment is not just a theoretical human ability but rather a way out of a dead end or a solution to a problem. However, judgment depends on acquired faith and recognition of the limits of reason. Judgment is a mental activity separate from reason and will. The liberation of the faculty of judgment requires the exercise of the faculty of thought. Doubt paves the way for judgment to overcome uncertainty and to find a source of satisfaction in a world that limits genuine action and freedom. Only those who engage in doubt and judgement can confront the uncertainties of practical thinking and the limits of objective truth, critically assess situations, and find a sense of fulfilment despite the constraints of external circumstances. This ability to form judgements enables us to overcome the limitations of external conditions and gain a sense of satisfaction and agency in a complex and often unpredictable world.

Doubt, therefore, questions certainties, including ritualised or superficial beliefs, and thus allows for a more authentic and personal understanding of faith. Regarding faith, doubtful judgment allows for practical ethical and moral decisions based on religious convictions. Believers even must doubt actions and beliefs to make judgements about how to apply their faith principles in concrete situations. Just as Arendt describes practice as based on opinions and beliefs that are not necessarily true, faith is a practical foundation for life that shapes actions and ethics, even if it cannot be objectively proven. Faith provides a guideline for living, like Arendt’s notion of opinions guiding action.

Many religious truths defy complete theoretical explanations and call for a practical conviction of faith that goes beyond what can be recognised by reason. They open up a space for faith as a response to the limits of human reason. Arendt views the ability to act as the central component of human freedom. Religious faith can be seen as a possible source of liberty because it enables people to act according to their own convictions and thus actively shape their circumstances and the world. Such religious faith is not lost in dogma but is active, reflective, and committed. Its dynamic, personal, and practical aspects lead through profound thinking and doubt to a meaningful and action-orientated faith.

3 Martin Luther and his faith

Examples show that doubt is viewed and discussed in different historical and cultural ways in various religions, both by prominent theological figures and in religious interpretations and practices.

A famous example within the Christian religion is the crisis of faith experienced by reformer Martin Luther during his time at the fortress of Coburg in 1530. This crisis was triggered by various factors, including the problematic personal situation he found himself in after the events in Augsburg. At the Imperial Diet there in the summer of 1530, Emperor Charles V had invited the old and new beliefs to be presented. Therefore, the first official presentation of the doctrine and practice of the Reformation was presented in the so-called Augsburg Confession. However, the supporters of the Reformation failed to change the religious practice of the German territories as a whole.

It was also a time of considerable unrest within the Catholic Church, characterised by corruption, excesses and abuses such as the sale of indulgences. These practices deeply disturbed Luther. His upbringing in a strictly religious environment, academic theological studies, engagement with humanistic science, the cultural and intellectual currents of the Renaissance, and the theological debates of his time clashed with his thoughts and beliefs and plunged him into deep doubt. Luther found no spiritual relief in traditional church practices. His crisis of faith ultimately led to the Reformation and the division of the Western church world. He broke with the Roman Catholic Church and demanded fundamental changes in Christian doctrine and practice.

The traditional Catholic Church placed the authority of the Church, its tradition and the weight of good works alongside the Holy Scriptures. On the other hand, Luther declared the justification of faith by the authority of the Bible alone. This faith is centred on the unbelievable fact of God’s incarnation and resurrection. The message of Holy Scripture does not demand obedience to the law and meritorious works but faith alone. Only faith is at the centre of the biblical message of salvation. Luther, therefore, insisted that the Bible alone should be the final authority in matters of faith and thus radically challenged Catholic doctrine. In his view, the individual can find salvation through faith in God’s grace alone, without needing additional good works. The resulting rejection of indulgences for salvation led to a particularly sharp division between Protestant and Catholic beliefs and changed Europe’s religious, social, and political fabric.

4. doubt in childhood trauma through religion

In a dogmatic or very restrictive religious environment, the unyielding demand to strictly adhere to rules and norms leads to deep shame when children experience that they can’t fulfil this demand. This shaming damages the child’s individual identity development and autonomy, causing inner conflicts, feelings of guilt and limited self-acceptance.

Especially in childhood, doubt plays a crucial role in religious integration precisely because of the internalised guilt and shame that are triggered by a rigid religious stance when children ask questions. Such children are taught that by doubting their faith, they sin and incur irredeemable guilt. The church fathers called doubt lukewarmness in faith – a mortal sin – and declared malice, rebellion, resentment, faint-heartedness, despair, blunt indifference to the commandments and regulations, and the “wandering of the mind in the direction of what is unlawful” to be their daughters (remarkably not: sons).

Children who grow up believing that their thoughts, feelings, desires, and needs are sinful or shameful internalise these beliefs and develop a negative self-image that damages self-confidence, self-love, and self-acceptance. They see themselves as flawed or bad. Beliefs, practices, and communities anchor such beliefs and core beliefs in children’s subconscious. These core beliefs are formed in the first years of life and shape the child’s brain structure. According to intersubjective theory, this is because recurring transactional patterns within the parent-child relationship lead to the formation of organisational patterns of the brain that shape unconscious relationships with other people and influence personality development. These patterns must not declare children’s doubts, needs and feelings as defective or unacceptable and plunge them into a lifelong vicious circle of shame, self-loathing, and further shame. Because children cannot harbour any doubts about their caregivers’ behaviour, they blame themselves for rejection by their parents and internalise negative beliefs about themselves, combined with a feeling of not being important or lovable. These profoundly ingrained core beliefs further deprive children of the courage to articulate their own needs and boundaries, as they believe they are responsible for their parents’ or community’s well-being.

The result is an inner conflict between their well-being and the expectations and needs of those around them. If children are forced to conform to their community’s beliefs and practices unconditionally, they cannot have any doubts about these teachings and practices. Instead, they doubt their own identity and autonomy. The suppression of doubt and the internalisation of dogmatic beliefs lead to a state of inner confusion and self-denial, in which children feel helpless and morally weak for the rest of their lives, just as Luther did at the age of 47. From today’s perspective, his crisis of faith could, therefore, undoubtedly be seen as a religious trauma.

A community that abuses authority, so children feel unloved or rejected, damages their relationship with the self and others. Children learn that “sins” are severely punished and that they must deny certain aspects of themselves to be “pure”. That prevents children from learning to accept themselves and recognise and express their needs.

For healthy development, children need to be lovingly mirrored by their carers, supported in building a stable sense of self-worth and experienced in recognising their childlike needs. Only an environment that offers space for honesty, openness and self-acceptance allows children to develop their personality freely, without feelings of guilt or self-denial. They must be allowed to question their own beliefs to develop their individual identity. Otherwise, beliefs, practices, and communities in childhood lead to lifelong psychological distortions

Summary

This post explores the complex relationships between religious belief, doubt, and child psychological development.

Doubt is a natural and essential part of human consciousness and thinking that encourages us to question beliefs and promote openness to new knowledge and learning. This process is crucial for psychological maturity and self-discovery.

How religious doubt is dealt with varies greatly between distinct cultures and belief systems. While some traditions see doubt as a means of deepening faith, others view it as threatening spiritual order. The post sheds light on how this approach influences psychological development, especially in childhood.

In strictly dogmatic religious environments, suppressing doubt leads to psychological conflict. Children who grow up in such environments experience inner conflicts, feelings of guilt and limited self-acceptance and learn that their questions and natural insecurities are despicable or even sinful.

The post draws on examples from different philosophical traditions, such as those of Zhuang Zhou and Hannah Arendt, to show how doubt is a critical force that shapes self-perception and engagement with external authorities.

Doubt questions certainties. Beliefs are not objective knowledge but practical convictions based on judgment. A living faith must, therefore, offer – not only to children – room for personal questioning and critical thinking as the basis for unrestricted judgment.

The decision horizon of this judgment is open. Theologians such as Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Gerhard Ebeling have viewed doubt as a critical force of faith vis-à-vis religious determinations and certainties while at the same time viewing religion as a life condition of faith. Russell’s position is equally committed to critical thinking and intellectual integrity but rejects a purely faith-based claim to trust and acceptance without rational justification.

Literature:

Afford, Peter. 2019. Therapy in the Age of Neuroscience: A Guide for Counsellors and Therapists. London – New York: Routledge.

Arendt, Hannah. 1981. The Life of the Mind. San Diego, New York, London: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Arendt, Hannah. 2012. Das Urteilen: Texte zu Kants politischer Philosophie; Dritter Teil Zu “Vom Leben des Geistes”. München: Piper.

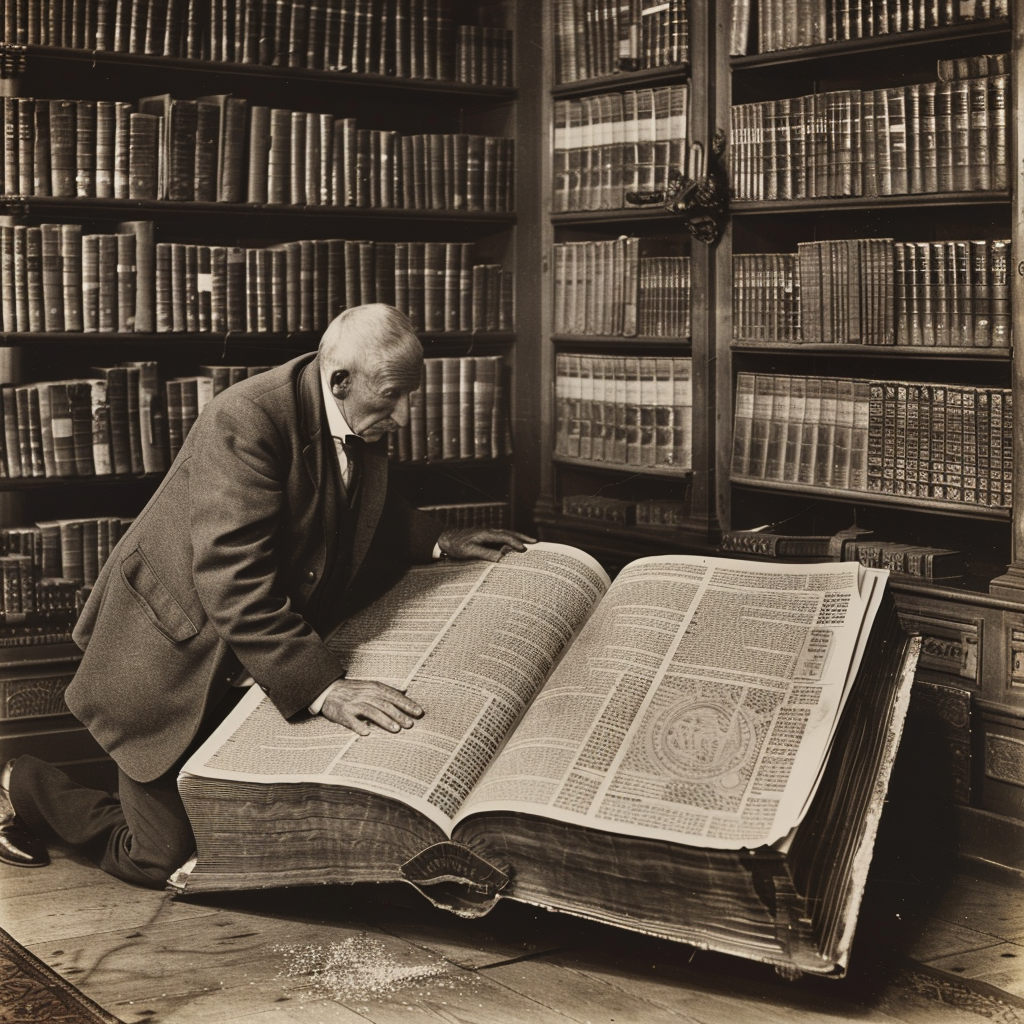

Blumenberg, Hans. 1986. Die Lesbarkeit der Welt. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Blumenberg, Hans. 1988. Work on Myth. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Blumenberg, Hans. 2001. Lebenszeit und Weltzeit. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Blumenberg, Hans. 2006. Arbeit am Mythos. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Boyer, Pascal. 2001. Et L’Homme Créa Les Dieux: Comment Expliquer La Religion. Paris: Robert Laffont.

Buber, Martin. 1995. Ich und Du. Stuttgart: Reclam.

Celano, Tommaso da. 2016. La Vita Di San Francesco D’Assisi (Italian Edition). Le Vie della Cristianità.

Chomsky, Noam. 2011. How the World Works (Real Story (Soft Skull Press)) (English Edition) Kindle Ausgabe. Soft Skull.

Denborough, David. 2017. Geschichten des Lebens neu gestalten. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Eliade, Mircea. 1954. Cosmos and History: The Myth of the Eternal Return. New York: Harper Torchbooks.

Eliade, Mircea. 1964. Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy. Penguin Books.

Eliade, Mircea. 1978. History of Religious Ideas, Volume 1: From the Stone Age to the Eleusinian Mysteries. Chicago : University of Chicago Press.

Eliade, Mircea. 1982. History of Religious Ideas, Volume 2: From Gautama Buddha to the Triumph of Christianity. University of Chicago Press.

Eliade, Mircea. 1988. History of Religious Ideas, Volume 3: From Muhammad to the Age of Reforms. University of Chicago Press.

Finch, Jamie Lee. 2019. You Are Your Own: A Reckoning With the Religious Trauma of Evangelical Christianity. Independently Published.

Foucault, Michel. 2009. Hermeneutik des Subjekts: Vorlesungen Am Collège de France (1981/82). Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Franz, Marie-Louise von. 2001. Psychotherapy. Shambhala.

Gadamer, Hans-Georg. 1990. Hermeneutik I: Wahrheit und Methode. Grundzüge Einer Philosophischen Hermeneutik (Gesammelte Werke 1). Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

Gadamer, Hans-Georg. 1993. Hermeneutik II: Wahrheit und Methode. Ergänzungen, Register (Gesammelte Werke 2). Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

Herpertz, Sabine. 2008. Störungsorientierte Psychotherapie. München: Urban&Fischer.

Iagher, Matei. 2018. “Beyond Consciousness: Psychology and Religious Experience in the Early Work of Mircea Eliade (1925-1932).” New Europe College Stefan Odobleja Program Yearbook (2017+ 18): 119–48.

Korsch, Dietrich, and Volker Leppin, Hrsg. 2020. Martin Luther – Biographie und Theologie. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude. 1962. Anthropologie Structurale. Paris: Librarie Plon.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude. 2018. Strukturale Anthropologie I. Suhrkamp.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude. 2019. Strukturale Anthropologie II. Suhrkamp.

Levine, Peter A., and Bessel Van der Kolk. 2015. Trauma and Memory: Brain and Body in a Search for the Living Past: A Practical Guide for Understanding and Working With Traumatic Memory. Berkely, California: North Atlantic Books.

Maxwell, Paul. 2022. The Trauma of Doctrine: New Calvinism, Religious Abuse, and the Experience of God. Lanham • Boulder • New York • London: Fortress Academic.

Moellendorf, Darrel. 2019. “Hope for Material Progress in the Age of the Anthropocene.” In The Moral Psychology of Hope, edited by Claudia Blöser, and Titus Stahl, 249–64. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Nussbaum, Martha C. 2012. The New Religious Intolerance. Overcoming the Politics of Fear in an Anxious Age. Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

O’Gieblyn, Meghan. 2021. God, Human, Animal, Machine: Technology, Metaphor, and the Search for Meaning. Anchor.

Otto, Rudolf. 1924. The Idea of the Holy. Ravenio Books.

Petersen, Brooke N. 2022. Religious Trauma: Queer Stories in Estrangement and Return. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books.

Peterson, Jordan B. 2002. Maps of Meaning: The Architecture of Belief (English Edition) Kindle Ausgabe. New York – London: Routledge.

Price, Max D. 2021. Evolution of a Taboo: Pigs and People in the Ancient Near East. New York: Oxford University Press, USA.

Rizzuto, Ana-Marie. 1979. Birth of the Living God: A Psychoanalytic Study. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press.

Russell, Bertrand, and Simon Blackburn. 2004. Why I Am Not a Christian: And Other Essays on Religion and Related Subjects. Psychology Press.

Sagan, Carl. 1997. The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark.

Schauer, Maggie, Thomas Elbert, and Frank Neuner. 2017. “Narrative Expositionstherapie (NET) für Menschen nach Gewalt und Flucht. Ein Einblick in das Verfahren.” Psychotherapeut 62 (4): 306–13.

Schiraldi, Glenn. 2009. The Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Sourcebook : A Guide to Healing, Recovery, and Growth: A Guide to Healing, Recovery, and Growth. New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

Scholem, Gershom. 1997. On the Kabbalah and Its Symbolism. New York: Schocken.

Stein, Alexandra. 2016. Terror, Love and Brainwashing: Attachment in Cults and Totalitarian Systems. Taylor & Francis.

Wikipedia-Autoren, s. Versionsgeschichte. 2024. “Religion.”