The sacred and child development

- The sacred and child development

- Introduction

- The sacred

- Children and the concept of the sacred

- Development of moral and ethical awareness

- Participation and identity formation

- Emotional and spiritual experiences

- When the sacred harms children

- The role of shame in religious communities

- Shame on religious education

- Religion, childhood trauma and the role of shame

- Conclusion

Introduction

In various belief systems, concepts of shame and the sacred are at the centre of religious experiences and related to ethics.

The sacred is defined by the existence of incorporeal, supernatural forces that are assumed by religions. These forces can be personal or impersonal, such as deities, spirits or laws such as Dao or Dharma. At the same time, religions presuppose that man is more than a physical being and has a connection to the supernatural in a dimension beyond ordinary consciousness, which is sanctified. Religion refers to all ideas, attitudes and actions towards a supernatural reality, whether as power, spirits, gods, the sacred or absolute, or simply the supernatural.

Regardless of how the respective belief system understands the sacred, the sacred plays a fundamental role in the root of ethics and morality and connects the human being with the higher in a unique, sacred way and thus becomes an integrative part of the human experience. Religion in societies is, therefore, not a purely individual matter but promotes communal connection and collective action within a society. Ethical and moral values conveyed by religions stabilise societies and ensure the survival of groups because they encourage prosocial behaviour and set social norms.

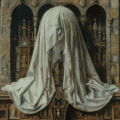

The sacred

In the context of religion and ethics, the question of the sacred plays an extraordinary role. The Protestant theologian Rudolf Otto described the religious feeling as a feeling of the supramundane (sensus numinis). He described four elements of this religious experience – the tremendum = the spectacle, the majestas = the overpowering, the energetic = the power, the will and the mystery = the “completely different”. At the core of his now-forgotten theory, Otto initially describes the sacred as an experience of the “wholly other”, a mixture of fascination and fear that immediately and intuitively captures human feeling. He describes this original, emotional experience of the sacred as an encounter with the numinous, both terrifying (tremendum) and attractive (fascinans). According to Otto, this original feeling of the sacred is later “moralised” through thought. By this, he means that the raw, immediate experience of the numinous is gradually integrated into the structures of human morality and ethics. This process of moralisation changes the original feeling so that it conforms to society’s cultural and ethical norms. People begin to associate the sacred with moral categories and concepts. That enables them to integrate religious experiences into their daily lives and ethical behaviour.

Shame as an emotional reaction arises when individuals violate their community’s social or religious norms, whether they are considered sacred or not. In many cultures and religions, however, crossing such boundaries is not only regarded as moral misconduct but also an offence against the sacred (sacrilege). Actions or thoughts interpreted as desecrating or disrespecting what is considered sacred arouse shame. It signals the violation of the sacred and serves as an incentive to return to the ground of accepted norms. Shame, therefore, has an essential social function in maintaining religious and moral order. It helps to keep behaviour within the boundaries defined by what is considered sacred.

Similar to the “moralisation of the sacred”, shame can also be moralised by embedding it in the framework of ethical considerations. In this way, the experience of shame leads people to act out of fear of social rejection and out of genuine moral conviction.

Children and the concept of the sacred

Children who grow up in a religious context encounter concepts of the sacred early in life that shape both their understanding of the world and their inner moral and ethical development.

Children learn a lot through observation and imitation. How the sacred is presented and honoured in their family and religious community offers them their first insights into what is considered particularly valuable or awe-inspiring: rituals, special festivals, sacred texts and places. Such experiences help children understand the world in terms of the sacred and the profane and provide them with a frame of reference for interpreting their spiritual experiences.

Development of moral and ethical awareness

In this way, children learn to regard certain things, actions or places as sacred, along with the associated norms and rules. This knowledge influences their development and provides a guideline for distinguishing right and wrong. The sacred appears as commandments in stories that teach important moral lessons. They teach children particular virtues such as honesty, compassion and obedience.

Participation and identity formation

By participating in the aforementioned religious rituals and festivals that honour the sacred, children feel part of their community if they respect its values and traditions. This participation becomes part of their social and religious identity as a sense of belonging.

Emotional and spiritual experiences

Children often experience the sacred in an immediate emotional way, with feelings of awe, wonder and curiosity merging into the core of a deeply religious experience. Such experiences comfort and guide children in difficult situations and awaken an understanding of a greater power or purpose.

When the sacred harms children

Children cannot form the concept of holiness from their own sensory experiences and must, therefore, learn it from caregivers and their community. If they experience a higher power as conciliatory, comforting and supportive, its omnipresence, omniscience and omnipotence give them courage. An invisible presence that knows everything punishes, avenges, and kills will instead generate unbearable, constant fear. Out of this fear of punishment or – particularly unbearable for children – abandonment, they do everything they can to avoid incurring any guilt and thus expose themselves to the vengeance of the Holy One. That mainly happens when the sacred and the expectations attached to it are rigidly and relentlessly organised within religious communities. It represents the core of spiritual abuse.

Shaming and punishment

In some religious parenting practices, mistakes or sins are threatened with harsh punishments, both physical and emotional. Children who are shamed or punished for perceived misbehaviour inevitably experience toxic shame embedded in an underlying sense of worthlessness.

Excessive demands due to religious expectations

If children are pressured to behave in a “holy” manner constantly or are expected to live up to unrealistic religious ideals, this awakens strong inner fears and self-doubt. Unfulfilled expectations damage their self-esteem and become the cause of long-term anxiety or depression.

Isolation and social exclusion

Not being able to fulfil the religious norms of one’s own community and at the same time experiencing that this inadequacy is socially isolated or ostracised awakens in children a terrible fear of being abandoned by their loved ones and exposed to a hostile world. Even in adulthood, this fear reinforces the feeling of being cut off and prevents any access to supportive relationships or networks outside the faith community.

Conflicts between personal identity and faith

Inner conflicts with unrelenting religious doctrines or practices create inner tensions that are almost unbearable. Such contradictions between personal feelings, thoughts and actions and rigid external expectations lead to an identity crisis and emotional pain.

Such traumatic experiences with the sacred in childhood damage mental health and well-being over the long term and permanently disrupt emotional regulation and interpersonal relationships.

The role of shame in religious communities

Some religious communities rely on shaming to persuade members to comply with moral laws and ethical requirements and to follow their respective traditions. In this case, the commandments of the highest authority threaten disobedience with punishments in this world or the hereafter or the loss of eternal salvation. However, violations of these rules can also be sanctioned by the community. Disobedience is exposed, and the offender is expelled from the community. In an appropriate natural environment, this can result not only in loneliness but also in death.

In such cases, shame serves as social control, stabilises psychologically and physically and promotes individual helpfulness and social improvement.

On the other hand, in authoritarian religious communities, fear and shame are potent instruments for controlling members. These communities instil a sense of shame in individuals in the conviction that they are inherently unworthy and deficient and can, therefore, only achieve salvation in the religious community. Adherence to religious doctrines thus becomes the basis for acceptance and survival. A dependency on the religious group develops.

In addition, such communities develop practices of publicly branding individuals who do not conform to or oppose the teachings or practices of the religion. Such practices may even require members to expose and shame themselves if they do not follow the expected norms or question the community’s beliefs.

That makes a strong impression on emotionally defenceless children who witness such shaming. They internalise feelings of guilt and the conviction of their inadequacies, and a cycle of shame and fear is set in motion. The fear of judgement and rejection prevents them from ever asking questions or expressing doubts. It keeps them permanently trapped in the cycle.

The fear of exclusion from the group creates pressure to behave well, discouraging spontaneity and independence of thought and action. Suppose individuals decide to leave such controlling religious communities in adulthood. In that case, the result is a traumatic experience of losing social support, a coherent worldview and any sense of meaning and purpose the community offered, along with a sense of lasting shame and guilt for the betrayal.

Shame on religious education

There are different views on the concept of shame in religious education, especially from the perspective of religious trauma.

According to Freud, religion stems from the need to defend against natural fears and to create a moral order to counteract desires such as killing and destruction. Although he regarded religion as a “collective neurosis“, he recognised its original function as a protection against anxiety because it explains inexplicable aspects of life. Freud’s perspective on religion is that of a “self-object”. However, Freud did not use this term. It comes from Heinz Kohut’s later self-psychology and refers to persons or objects in an individual’s environment that serve to regulate and maintain the sense of self. Self-objects such as religion are not literally parts of the self but are psychologically experienced as if they were part of the self. They, therefore, play a crucial role in the development and maintenance of self-esteem and the emotional balance that supports the self-concept and provides explanations that go beyond scientific understanding.

In contrast, authoritarian religions serve the cycle mentioned above of shame and fear, for example, through teachings of original sin and eternal damnation. Children then feel guilty, responsible for their actions and, at the same time, powerless. Emphasising shame in religious education, for example, in fundamentalist Christianity, leads to trauma, inner fragmentation and psychological suffering as children struggle unsuccessfully to reconcile their self-perception and self-acceptance with religious teachings.

Religion, childhood trauma and the role of shame

Childhood trauma and religious trauma are closely linked. Like physical, sexual and emotional abuse or neglect, spiritual abuse has been shown to have long-term consequences, including increased rates of psychiatric disorders in adulthood. Spiritual trauma affects neural development and the immune system and causes depression and anxiety.

Religious trauma, i.e. the emotional and psychological impact of leaving religious beliefs in adulthood, creates an additional dimension of traumatisation with a shattering sense of identity and well-being. Leaving an authoritarian or fear-based religious community creates a cognitive dissonance that can become unbearable

The horrors of violating taboos and their consequences go back a long way in the development of mankind. In indigenous societies, group members are expected to recognise the laws of existence and act accordingly. Sanctions from the community for breaking the rules are possible, but the symbolic dimension of such misdeeds is even more critical.

In cultures where magic and taboo are deeply rooted in the belief system, the idea of being influenced by supernatural forces becomes a real and powerful truth. The belief in the power of a curse after a taboo violation can be so overwhelming that it causes physiological reactions that can even lead to death. The death caused by the individual’s conviction of being cursed after a taboo violation is reinforced by the same conviction in the community as in an echo chamber: the reaction of the community, the confirmation of the curse by shamans or healers and the resulting isolation of the victim reinforce the conviction of the person concerned that their fate is sealed. Religious and cultural beliefs are real and powerful for their followers, regardless of how outsiders perceive them.

Religion and public condemnation, therefore, have considerable similarities, such as fierce intolerance of dissenters and their ostracism. Public shaming and exclusion from a religious community following a violation of norms have severe social and metaphysical consequences for the individual.

However, traumatising religious experiences lead to inner turmoil, anxiety and depression, even in adults, with difficulties in restoring their own sense of self and reality. The traces of spiritual abuse in children are correspondingly more profound. Trauma in childhood caused by contact with toxic religious teachings inhibits normal stages of development and cognitive, social, emotional and moral growth. Affected children face challenges in critical thinking, decision-making and rebuilding their self-confidence after leaving traumatising beliefs and communities.

Conclusion

The tension between the sacred and shame in the individual religious experience and child development is complex. It has far-reaching effects on the psychological health and social integration of children.

The sacred plays a fundamental role in children’s identity development in religious communities, offering them a frame of reference for the supernatural and, through its veneration, fostering the connection of the individual to something greater than the self. However, interaction with the sacred, especially in childhood, also harbours risks, such as rigid expectations and the threat of isolation after breaking the rules.

Shame, as a reaction to the violation of the sacred, not only serves to maintain social order but can also cause psychological trauma if it is not experienced in the context of supportive community practices. Especially in childhood, toxic shame induced by the sacred leaves deep scars, from fear and insecurity to long-term emotional and social problems.

We must bear in mind the relationship between the subject, truth and the practices of self-examination and self-improvement if we are to understand the relationship between the sacred and shame.

The intersection of religious upbringing, shame and internalised guilt shapes self-perception and the relationship to faith. Contradictory messages of sin, forgiveness and the pursuit of self-correction within religious communities impose a burden of shame on children that they must carry with them and that permanently shape their view of themselves and their spiritual path.

A deep understanding of the interactions between sacredness, shame and religious practice is a prerequisite for understanding the hidden psychological effects of spiritual abuse. This knowledge is not only crucial for the mental health of children but also for the design of educational and support programmes within communities. The ‘moralisation’ of the sacred, the integration of its direct experience into the structures of human morality and ethics, shows that the individual’s relationship to religious and cultural norms is dynamic and requires constant reflection and adaptation. Children who grow up in an environment that teaches them to view the sacred as a source of comfort and moral guidance develop healthy self-esteem and social skills. Overexposure to these concepts, coupled with fear of divine punishment or community exclusion, on the other hand, leads to a distortion of this development.

In education and community practice, there must be a balance between respect for the sacred and recognition of individual emotional and psychological boundaries to enable the child’s healthy development and integration into its social and spiritual environment.

Literature:

Afford, Peter. 2019. Therapy in the Age of Neuroscience: A Guide for Counsellors and Therapists. London – New York: Routledge.

Blumenberg, Hans. 1986. Die Lesbarkeit Der Welt. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Blumenberg, Hans. 1988. Work on Myth. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Blumenberg, Hans. 2001. Lebenszeit Und Weltzeit. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Blumenberg, Hans. 2006. Arbeit Am Mythos. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Boyer, Pascal. 2001. Et L’Homme Créa Les Dieux: Comment Expliquer La Religion. Paris: Robert Laffont.

Buber, Martin. 1995. Ich Und Du. Stuttgart: Reclam.

Chomsky, Noam. 2011. How the World Works (Real Story (Soft Skull Press)) (English Edition) Kindle Ausgabe. Soft Skull.

Denborough, David. 2017. Geschichten Des Lebens Neu Gestalten. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Eliade, Mircea. 1954. Cosmos and History: The Myth of the Eternal Return. New York: Harper Torchbooks.

Eliade, Mircea. 1964. Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy. Penguin Books.

Eliade, Mircea. 1978. History of Religious Ideas, Volume 1: From the Stone Age to the Eleusinian Mysteries. Chicago : University of Chicago Press.

Eliade, Mircea. 1982. History of Religious Ideas, Volume 2: From Gautama Buddha to the Triumph of Christianity. University of Chicago Press.

Eliade, Mircea. 1988. History of Religious Ideas, Volume 3: From Muhammad to the Age of Reforms. University of Chicago Press.

Finch, Jamie Lee. 2019. You Are Your Own: A Reckoning With the Religious Trauma of Evangelical Christianity. Independently Published.

Foucault, Michel. 2009. Hermeneutik Des Subjekts: Vorlesungen Am Collège De France (1981/82). Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Franz, Marie-Louise von. 2001. Psychotherapy. Shambhala.

Gadamer, Hans-Georg. 1990. Hermeneutik I: Wahrheit Und Methode. Grundzüge Einer Philosophischen Hermeneutik (Gesammelte Werke 1). Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

Gadamer, Hans-Georg. 1993. Hermeneutik Ii: Wahrheit Und Methode. Ergänzungen, Register (Gesammelte Werke 2). Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

Herpertz, Sabine. 2008. Störungsorientierte Psychotherapie. München: Urban&Fischer.

Iagher, Matei. 2018. “Beyond Consciousness: Psychology and Religious Experience in the Early Work of Mircea Eliade (1925-1932).” New Europe College Stefan Odobleja Program Yearbook (2017+ 18): 119–48.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude. 1962. Anthropologie Structurale. Paris: Librarie Plon.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude. 2018. Strukturale Anthropologie I. Suhrkamp.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude. 2019. Strukturale Anthropologie Ii. Suhrkamp.

Levine, Peter A., and Bessel Van der Kolk. 2015. Trauma and Memory: Brain and Body in a Search for the Living Past: A Practical Guide for Understanding and Working With Traumatic Memory. Berkely, California: North Atlantic Books.

Maxwell, Paul. 2022. The Trauma of Doctrine: New Calvinism, Religious Abuse, and the Experience of God. Lanham • Boulder • New York • London: Fortress Academic.

Moellendorf, Darrel. 2019. “Hope for Material Progress in the Age of the Anthropocene.” In The Moral Psychology of Hope, edited by Claudia Blöser, and Titus Stahl, 249–64. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Nussbaum, Martha C. 2012. The New Religious Intolerance. Overcoming the Politics of Fear in an Anxious Age. Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

O’Gieblyn, Meghan. 2021. God, Human, Animal, Machine: Technology, Metaphor, and the Search for Meaning. Anchor.

Otto, Rudolf. 1924. The Idea of the Holy. Ravenio Books.

Petersen, Brooke N. 2022. Religious Trauma: Queer Stories in Estrangement and Return. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books.

Peterson, Jordan B. 2002. Maps of Meaning: The Architecture of Belief (English Edition) Kindle Ausgabe. New York – London: Routledge.

Price, Max D. 2021. Evolution of a Taboo: Pigs and People in the Ancient Near East. New York: Oxford University Press, USA.

Rizzuto, Ana-Marie. 1979. Birth of the Living God: A Psychoanalytic Study. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press.

Russell, Bertrand, and Simon Blackburn. 2004. Why I Am Not a Christian: And Other Essays on Religion and Related Subjects. Psychology Press.

Sagan, Carl. 1997. The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark.

Schauer, Maggie, Thomas Elbert, and Frank Neuner. 2017. “Narrative Expositionstherapie (NET) für Menschen nach Gewalt und Flucht. Ein Einblick in das Verfahren.” Psychotherapeut 62 (4): 306–13.

Schiraldi, Glenn. 2009. The Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Sourcebook : A Guide to Healing, Recovery, and Growth: A Guide to Healing, Recovery, and Growth. New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

Scholem, Gershom. 1997. On the Kabbalah and Its Symbolism. New York: Schocken.

Stein, Alexandra. 2016. Terror, Love and Brainwashing: Attachment in Cults and Totalitarian Systems. Taylor & Francis.

Wikipedia-Autoren, s. Versionsgeschichte. 2024. “Religion.”