- Psychological and social roots of shame

- Introduction

- Origins of shame

- Neurobiology of shame

- Psychological and social aspects of shame

- Social roots of toxic shame

- Psychological roots of shame

- Toxic shame

- Fundamental beliefs and patterns of behaviour and experience of shame

- Effects of Toxic Shame

- Psychotherapy for toxic shame

- Exercises

- Conclusion

Introduction

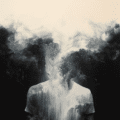

Imagine your every action and thought being constantly judged by an unseen audience. Such constant judgement will lead to a deep-rooted sense of shame that questions your very self. That is toxic shame.

Shame is a universal feeling that we all recognise. But when it turns into the destructive form described, it has a devastating impact on our self-image and our relationships.

In this post, we’ll dive into the origins of toxic shame and look at its psychological and social roots. We will explore historical examples and offer exercises to identify personal experiences of toxic shame.

Origins of shame

The origins of shame are complex and can be viewed from different perspectives. Different perspectives offer insights into the origins of shame from linguistic, religious, existential, social, evolutionary and psychological perspectives. (There is a separate article on the history of shame here on the WikiBlog).

Indo-European origins

The word “shame” is derived from the Indo-European word kam/kem, which means “to hide” or “to conceal”.

Religious texts

It is not only the story of Adam and Eve in Paradise that illustrates the origin of shame in religious contexts.

Existential origins

Shame is a fundamental and deeply rooted emotion related to the human condition of being aware of one’s insignificance and helplessness in the vast cosmos.

Genetics

Shame is a genetic predisposition that predisposes to socially responsible behaviour.

Neurobiology of shame

The neurobiology of shame describes the processes in the brain and body when shame is experienced. Shame is a complex emotion associated with various neurobiological changes in the body.

For example, research suggests that shame is associated with an increase in cortisol levels. Cortisol is a stress hormone that helps motivate people to respond to a threat. It has also been found that shame increases the activity of other messenger substances (so-called pro-inflammatory cytokines) in the body, thus promoting social withdrawal behaviour.

Shame appears to be rooted in the brain’s right hemisphere, which is associated with social and emotional processing. Therefore, researchers suggest a link between shame and emotion regulation and emphasise the importance of early life experiences and attachment relationships in the development of shame. The brain’s response to shame and its regulation is influenced by the quality of early care experiences, particularly in the context of the parent-child relationship. This role of the right hemisphere in the processing of shame experiences explains the significance of shame in the context of relationship experience and society.

Shame is related to the human condition and the evaluation of the self. It arises from early life experiences and disturbances in attachments to attachment figures.

Toxic shame is, therefore, not only shaped by personal experiences but also by cultural and social norms. Stereotypes, stigmatisation and unrealistic expectations can cause people to feel ashamed of aspects of themselves that do not conform to current standards.

Social roots of toxic shame

As a social emotion, shame arises from an individual’s awareness of being socially judged while not conforming to social expectations and norms. Shame is an internalised reaction to external judgement and reflects negative self-perception.

Shame is deeply embedded in the social organisation of daily behaviour. It serves to constrain individual behaviour in society and elicits public reactions to actions that are considered inappropriate or problematic. The concept of shame arises because the self is inherently social. Sociologists have emphasised that the self is shaped and formed through interactions with others and is closely linked to social norms, values and cultural context.

It becomes toxic when it damages self-esteem. From a social perspective, toxic shame is also influenced by cultural and social norms. In particular, clichés, stereotypes, stigmatisation and unrealistic expectations cause people to feel ashamed of parts of themselves that do not meet “ideal” standards.

A look at history shows how toxic shame can be culturally rooted.

Shame and social standing

Aristotle already regarded shame as an emotion closely linked to social prestige and the pursuit of honour. He discusses shame in the context of his concept of “thymos”. That is what he calls a fundamental desire for social prestige. Aristotle argues that shame is a social emotion one feels when one’s social value is denied or insulted. It is associated with pursuing honour and avoiding actions or behaviours that would diminish one’s social standing. In other words, it is a fear or pain that arises when actions or behaviour threaten to damage one’s reputation. A painful loss of power is then experienced in the eyes of a real or imagined observer.

Shame, therefore, plays a vital role in understanding moral rules. It gives individuals a sense of who they are and how they relate to others. Unlike guilt, which focuses on the harm done to others, shame draws attention to oneself and helps understand and reshape one’s behaviour and the world in which one lives. Like guilt, shame has an ethical content that allows individuals to reflect on their actions and their moral consequences. Shame leads to internalisation and becomes a tool for personal growth and moral development, which, step by step, builds up increasingly ethical behaviour from shameful occasions.

Shame and guilt

It is, therefore, not surprising that shame and guilt occur particularly frequently in art and literature, and usually together. However, research suggests that shame and guilt are different emotions, even if they have similarities.

Shame is self-centred but needs the gaze of others. It is triggered by the fact that one’s own shortcomings or transgressions are revealed or may be revealed to others. It is often accompanied by a feeling of worthlessness, powerlessness and the desire to hide or escape. Shame is closely linked to self-assessment and perceiving oneself as inadequate or unworthy.

On the other hand, feelings of guilt are rooted in a sense of responsibility for a moral transgression. That is usually associated with feelings of regret or remorse and a focus on the specific behaviour or action that caused the guilt. Feelings of guilt often motivate attempts to make amends, such as confession, apology or an attempt to undo the harm done.

Although shame and guilt differ in intensity and focus, they share some common characteristics. Certain behaviours or norm violations can trigger both, and the situations that evoke them can be pretty similar. Both can be triggered by moral and non-moral failures as well as violations of social conventions.

The difference between shame and guilt is, therefore, not the nature of the transgression or the situation’s circumstances but how the transgression and circumstances are interpreted. Shame focuses on one’s self, whereby the behaviour is seen as an expression of a flawed self, whereas guilt focuses on the wrongdoing and does not directly concern one’s self-concept.

Shame as an intersubjective feeling

Shame involves a confrontation between an observing object and the external reality or an (imaginary) object with the inner reality. The subject of shame is perceived as threatening and superior, as with Aristotle, but also as necessary for developing relationships. This experience begins long before mature self-awareness, in early childhood, where shame indicates a need for self-transformation that seeks to fulfil the assumed intention of a caregiver.

In Sartre’s existential-ontological view, shame is, therefore, fundamentally linked to the gaze and judgement of others. Sartre says: “I am ashamed of others”, thus emphasising the importance of the perception of others for the feeling of shame. This view emphasises the role of shame in recognising oneself as an inferior and dependent object for others.

Similarly, shame is influenced by one’s subjective experience of oneself in relation to the norms and expectations of society. Shame acts as a medium of social control that perpetuates norms and reinforces social inequality. The experience of shame involves imagining the judgements of others and conforming to the prevailing social norms. Shame is thus inherently intersubjective, as one perceives oneself through the eyes of others and feels the weight of their judgment.

Psychological roots of shame

Shame is one of the self-centred emotions, including guilt, embarrassment and pride. It is linked to self-judgement and leads to a feeling of humiliation or sorrow.

Psychodynamic theories assume that shame arises from conflicts between the ego, the ego ideal and the superego. Early life experiences and dysfunctional relationships with attachment figures, therefore, also contribute to feelings of shame.

Shame and perfectionism

Perfectionists tend to feel shame – mainly due to their all-or-nothing thinking and their tendency to generalise failures. Perfectionists make a whole chain of equations:

- They are convinced that performances that are not perfect must be seen as failures.

- They interpret their mistakes and failures as a reflection of themselves and that only perfection can have value.

- Conversely, they regard every less-than-perfect result as proof of their own worthlessness.

Preoccupation with the (presumed or expressed) standards and judgements of other people is particularly associated with susceptibility to experiences of shame. Perfectionists experience shame through the presumed evaluation of their person by others, and they can feel like failures overall. Because of this tendency of perfectionists to base their self-worth on external judgements and fear of not being perfect, there is a constant need to meet impossibly high standards.

Interestingly, in contrast, perfectionists often experience less guilt for certain behaviours as they focus more on their reputation and their evaluation than on the impact on others.

Toxic shame

Toxic shame arises in childhood from a mismatch between the basic need for attachment and the inability of carers to respond appropriately. Beginning after birth, all children learn to adapt to cues to establish and maintain attachment, whereby they must sometimes assert or suppress their own needs and develop a sense of self from their experience of self and relationships, which is also based on the reactions of others.

Dependence on external validation and the need to be perfect in order to feel valuable contribute particularly to toxic shame. When a child is exposed to constant criticism, neglect or abuse, they can’t help but develop a deep-rooted belief that there is something fundamentally wrong with them. This conviction is the essence of toxic shame.

Shame is rooted in family upbringing through various factors and dynamics. Here are some critical points:

Parenting style

It has been disproven that harsh or shaming parenting is the only cause of shame. Many people who suffer from chronic shame can find no evidence of such parenting in their childhood. Instead, their parents were too fearful or unable to provide their children with a nurturing and supportive environment.

Emotional neglect and interference

It remains the case, however, that in families with toxic shame, blame, mistrust, emotional neglect or verbal abuse are often the norm. Family members live in silos of emotional isolation, keeping secrets from each other. Shame becomes a lonely secret that is dealt with in different ways. This culture of secrecy and emotional dysregulation perpetuates shame within the family.

Attachment disorder

Shame is described as a relational trauma, especially in the context of a disturbed emotional relationship with essential attachment figures. It leads to a fragile, contradictory self-image, particularly through the lack of a coordinated response or effective regulation of relationships and feelings within the family. Thus, shame becomes deeply rooted in the individual’s relationship history.

Lack of empathy

Children do not feel seen and understood by their parents or siblings without understanding and relationships within a family. This lack of coordinated responsiveness and emotional connection contributes to the development and perpetuation of toxic shame.

Dynamics such as emotional neglect or assault, lack of emotional connection and the transmission of shame across generations shape an individual’s self-image, self-esteem and vulnerability to shame.

Inherited shame

Adults can also project their own wounded inner child onto children with disparaging statements about their bodies, minds or abilities. These value statements erode the child’s fragile sense of self-worth and lead to low self-esteem during puberty and beyond. Children internalise this “inherited shame” from adults and create a significant gap between the individual’s self-perceptions and observable reality.

Fundamental beliefs and patterns of behaviour and experience of shame

Precipitates of early relationships and experiences are internalised as “working models” and basic beliefs. Corresponding to them are connections of neurons in the brain that are so stable that triggers automatically activate them. Harmful core beliefs arise as a result of inadequately satisfied basic needs:

Secure attachment to other people,

Autonomy, competence and identity,

realistic boundaries and self-control,

freedom and expression of justified needs and emotions, and

spontaneity and play.

In addition, there are internalised evaluations and patterns of coping behaviour. The latter represent reactions to the original working models intended to prevent the activation of painful beliefs as far as possible.

Basic beliefs are stable and often remain unconscious and, in any case, in the background. Perceptible patterns only emerge from currently activated experience states and associated behaviour. These activation patterns can change rapidly depending on the situation. They are, therefore, not “sub-personalities” but an expression of activated basic convictions. However, they are directly observable and, thus, more accessible both for those affected and the others. (Basic convictions themselves can only be deduced indirectly from the biography). There are various such patterns. Even parental images can also be internalised as such patterns, such as punitive or demanding parents. Coping patterns are: Subordination, avoidance of feelings through distance, overcompensation, arrogance, bullying, trickery, or an obsessive need for control.

Of course, there is also a healthy activation pattern. Several of these patterns are particularly associated with shame:

Mistrust

Feelings of shame and mistrust towards others characterise this pattern. People who activate this pattern feel ashamed and even undeserving of love and support. That makes it difficult to build trusting relationships.

Anger

This pattern involves intense feelings of anger and aggression towards oneself and others. Shame about feeling defective or inadequate fuels this anger.

Impulsiveness

This pattern leads to difficulties with impulse control and self-regulation. Shame can then result from impulsive and inappropriate or harmful behaviour.

Despair

Feelings of sadness, loneliness and despair characterise this pattern. Shame then arises from feeling undeserving of happiness and fulfilment and from self-blame.

Shame is, therefore, embedded in attachment-related beliefs and patterns of psychological experience.

Effects of Toxic Shame

Shame is accompanied by feelings of vulnerability, inferiority and concern for the opinions of others. Fear of judgement and rejection activates these harmful coping patterns, resulting in avoidance, aggression or self-deprecation to protect self-esteem and avoid further shaming. Psychology thus recognises numerous effects of toxic shame.

Body shame

Feelings such as shame, sadness and fear can only be experienced through self- and body awareness.

Eating disorders

Bulimia nervosa is associated with depression and shame and is related to self-perception and body image. In studies, people with anorexia and bulimia nervosa have higher scores for global shame than sufferers of anxiety disorders and depression.

Social phobias

Shame has been identified as a key emotional symptom of social phobias. People with social phobia avoid social gatherings for fear of rejection because they do not trust themselves to fulfil the expectations of others. They feel ashamed because they fear that their nervousness or anxiety could be recognised. Shame increases their anxiety even further.

Self-devaluation

Toxic shame leads to an overall negative self-perception and self-assessment in which those affected internalise their shame and believe that they are fundamentally flawed or worthless. That damages their self-esteem and general well-being.

Avoidance

Avoidance behaviour then serves to escape the discomfort and emotional pain associated with toxic shame. Social interactions, in particular, are avoided, limiting opportunities for relationships and growth. Toxic shame, therefore, has a detrimental effect on relationships in various ways.

Relationship dysfunction

The fear of shame can lead to the concealment of personal information. That hinders the development of open and trusting relationships. Shame can thus lead to feelings of disconnectedness. Those affected appear just as unattainable for others as the others occur to those affected.

Accusations

As described above, shame can also manifest itself in outwardly directed anger and blame. These sufferers direct their anger towards others as a defence mechanism to protect their self-esteem and distract from their own shame.

False pride

Shame often prevents people from seeking help because they fear rejection or embarrassment. That can even lead to delayed medical treatment with potentially adverse health consequences.

Psychotherapy for toxic shame

Psychotherapy addresses toxic shame in a variety of ways. Here are some examples:

Harmful moments

One approach is recognising and dealing with ‘harmful moments’ in everyday life. These moments refer to times when those affected are alone and repeatedly experience negative feelings of shame and guilt, loneliness and hopelessness. In such moments, it is crucial to learn how to deal with these strong emotions appropriately and to overcome self-harming behaviour or even suicidal thoughts.

Imagination exercises

Imagination techniques are used to process painful or traumatic scenes from the past. These scenes are rewritten to promote the healing of the underlying beliefs. Learning how these issues from the past play out in one’s present life makes it possible to change the underlying beliefs.

Reparenting

Those affected need support to learn to bear the pain of hurt and loneliness without resorting to self-soothing or compulsive behaviours. Psychotherapy works to heal patterns of experience of the “wounded child”. “Reparenting” serves this purpose. The term sounds strange. But in therapy, it is actually possible to a certain extent to fulfil basic emotional needs retrospectively and thus gradually and successfully leave trauma behind.

Exercises

If you would like to explore your own experiences with toxic shame, the following exercises may be helpful:

Childhood memories

Think back to your childhood. Were there moments when you felt deeply ashamed? How did these experiences shape your self-perception?

Journaling

Start keeping a diary of moments when you felt ashamed. Write down what happened and how it made you feel. Look for patterns.

Observe your inner monologue

Pay attention to your inner monologue and self-talk. Do self-criticism and shame characterise them? How could you reshape them with more self-compassion?

Conclusion

Shame is both individual and cultural. It is far more than just a personal feeling. It is also a reflection of the society we live in.

When it comes to overcoming toxic shame, understanding its historical, psychological and social roots can help us move towards greater self-acceptance and compassion. They serve as a starting point for a deeper understanding and more conscious engagement with this complex emotion.”

Sources:

Ashley, Patti. 2020. Shame-Informed Therapy: Treatment Strategies to Overcome Core Shame and Reconstruct the Authentic Self. Eau Claire, Wisconsin: Pesi Publishing & Media.

Austin, Sue. 2016. “Working with chronic and relentless self‐hatred, self‐harm and existential shame: a clinical study and reflections.” Journal of Analytical Psychology 61 (1): 24–43.

Bach, Bo, and Joan M. Farrell. 2018. “Schemas and modes in borderline personality disorder: The mistrustful, shameful, angry, impulsive, and unhappy child.” Psychiatry Research 259 323–29.

Boddice, Rob. 2019. A History of Feelings. London: Reaktion Books.

Brown, Brené. 2006. “Shame resilience theory: A grounded theory study on women and shame.” Families in Society 87 (1): 43–52.

Clark, Timothy R. “The 4 Stages of Psychological Safety.”

Collins, George N., and Andrew Adleman. 2011. Breaking the Cycle: Free Yourself From Sex Addiction, Porn Obsession, and Shame. New Harbinger Publications.

De Paola, Heitor. 2001. “Envy, jealousy and shame.” The International Journal of Psychoanalysis 82 381–84.

DeYoung, Patricia A. 2021. Understanding and Treating Chronic Shame: Healing Right Brain Relational Trauma. New York: Routledge.

English, Fanita. 1975. “Shame and social control.” Transactional Analysis Journal 5 (1): 24–28.

Erskine, Richard G., Barbara Clark, Kenneth R. Evans, Carl Goldberg, Hanna Hyams, Samuel James, and Marye O’Reilly-Knapp. 1994. “The dynamics of shame: A roundtable discussion.” Transactional Analysis Journal 24 (2): 80–85.

Frost, Ulrike, Micha Strack, Klaus-Thomas Kronmüller, Annette Stefini, Hildegard Horn, Klaus Winkelmann, Hinrich Bents, Ursula Rutz, and Günter Reich. 2014. “Scham und Familienbeziehungen bei Bulimie. Mediationsanalyse zu Essstörungssymptomen und psychischer Belastung.” Psychotherapeut 59 (1): 38–45.

Greenberg, Tamara McClintock. 2022. The Complex Ptsd Coping Skills Workbook: An Evidence-Based Approach to Manage Fear and Anger, Build Confidence, and Reclaim Your Identity. New Harbinger Publications.

Heller, Laurence, and Aline LaPierre. 2012. Healing Developmental Trauma: How Early Trauma Affects Self-Regulation, Self-Image, and the Capacity for Relationship. Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books.

Hirsch, Mathias. 2008. “Scham und Schuld – Sein und Tun.” Psychotherapeut 53 (3): 177–84.

Klein, Melanie. 1984. Love, Guilt, and Reparation, and Other Works, 1921-1945. New York: The Free Press.

Konstam, Varda, Miriam Chernoff, and Sara Deveney. 2001. “Toward forgiveness: The role of shame, guilt anger, and empathy.” Counseling and Values 46 26–39.

Lammers, Maren. 2020. Scham und Schuld – Behandlungsmodule für den Therapiealltag. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta.

MacKenzie, Jackson. 2019. Whole Again: Healing Your Heart and Rediscovering Your True Self After Toxic Relationships and Emotional Abuse. Penguin.

Mayer, Claude-Hélène, and Elisabeth Vanderheiden. 2019. The Bright Side of Shame: Transforming and Growing Through Practical Applications in Cultural Contexts. Cham: Springer Nature.

Miller, Susan. 2013. Shame in Context. Routledge.

Morrison, Andrew P. 1983. “Shame, Ideal Self, and Narcissism.” Contemporary Psychoanalysis 19 (2): 295–318.

Rafaeli, Eshkol, Jeffrey E. Young, and David P. Bernstein. 2013. Schematherapie. Junfermann Verlag GmbH.

Roediger, Eckhard. 2016. Schematherapie: Grundlagen, Modell und Praxis. Stuttgart: Schattauer.

Saenz, Victor. 2018. “Shame and Honor: Aristotle’s Thumos as a Basic Desire.” Apeiron 51 (1): 73–95.

Scheff, Thomas J. 2000. “Shame and the social bond: A sociological theory.” Sociological Theory 18 (1): 84–99.

Scheff, Thomas J. 2003. “Shame in self and society.” Symbolic interaction 26 (2): 239–62.

Schumacher, Bernard N. 2014. Jean-Paul Sartre: Das Sein Und Das Nichts Kindle Ausgabe. Walter de Gruyter.

Stahl, Stefanie. 2020. The Child in You: The Breakthrough Method for Bringing Out Your Authentic Self. London: Penguin.

Steiner, John. 2015. “Seeing and being seen: Shame in the clinical situation.” The International Journal of Psychoanalysis 96 (6): 1589–601.

Stemper, Dirk. 2023. Toxic Guilt and Shame: The Practical Workbook for Self-Acceptance. Berlin: Psychologie Halensee.

Stolorow, Robert D. 2010. “The Shame Family: An Outline of the Phenomenology of Patterns of Emotional Experience That Have Shame at Their Core.” International Journal of Psychoanalytic Self Psychology 5 (3): 367–68.

Stolorow, Robert D. 2011. “Toward Greater Authenticity: From Shame to Existential Guilt, Anxiety, and Grief.” International Journal of Psychoanalytic Self Psychology 6 (2): 285–87.

Tangney, June P. 2002. “Perfectionism and the Self-Conscious Emotions: Shame, Guilt, Embarrassment, and Pride.” In Perfectionism: Theory, research, and treatment, 199–215. Washington: American Psychological Association.

Tangney, June P., Roland S. Miller, Laura Flicker, and Deborah H. Barlow. 1996. “Are shame, guilt, and embarrassment distinct emotions?” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 70 (6): 1256–69.

Tiedemann, Jens L. 2008. “Die intersubjektive Natur der Scham.” Forum der Psychoanalyse 24 (3): 246–63.

Van Vliet, K. Jessica. 2008. “Shame and resilience in adulthood: A grounded theory study.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 55 (2): 233–45.

Wells, Marolyn, Cheryl Glickauf-Hughes, and Rebecca Jones. 1999. “Codependency: A grass roots construct’s relationship to shame-proneness, low self-esteem, and childhood parentification.” The American Journal of Family Therapy 27 (1): 63–71.

Williams, Bernard. 2015. Scham, Schuld und Notwendigkeit: Eine Wiederbelebung antiker Begriffe der Moral. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Wurmser, Leon. 2011. Die Maske Der Scham: Die Psychoanalyse von Schamaffekten und Schamkonflikten. Berlin – Heidelberg: Springer.