Childhood trauma responses: Neurobiology

- Childhood trauma responses: Neurobiology

- Definition of a traumatic situation according to DSM-IV

- Childhood trauma responses: Fear

- Childhood trauma reactions: Nightmares, Flashbacks, Intrusions

- Childhood trauma reactions: Persistently heightened physiological arousal (hypervigilance)

- Childhood trauma reactions: avoidance behaviour

- Childhood trauma reactions: trauma identity

To understand what childhood trauma reactions do in the brain, we need to understand what trauma is in the first place. For example, subjective conditions must also be distinguished in addition to objective conditions. A situation is objectively traumatic if the event caused extreme stress for most people, an armed robbery, for example. In addition, there are also subjective conditions of traumatization: the experience of extreme fear, helplessness, or powerlessness. Accordingly, the current definition of traumatization according to DSM-IV for criterion A of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) stipulates that both objective (A1) and subjective criteria (A2) must be fulfilled.

Definition of a traumatic situation according to DSM-IV

The affected person was exposed to a situation in which the following conditions were met:

The person was confronted, either themselves or as a witness, with an event involving death, the threat of death or a severe threat to the physical integrity, of him/herself or other people (criterion A1).

The affected person reacted with intense fear, helplessness, or horror (criterion A2).

What is inexplicably missing is the threat to psychological integrity. However, it is essential that the DSM-IV also recognizes witnessing a severe threat as objectively traumatizing. Both are factors of great importance for childhood trauma reactions and complex post-traumatic stress disorder (cPTSD) after childhood trauma, which rarely involves a single trauma situation, but regrettably usually repeated abusive situations over long periods.

Childhood trauma responses: Fear

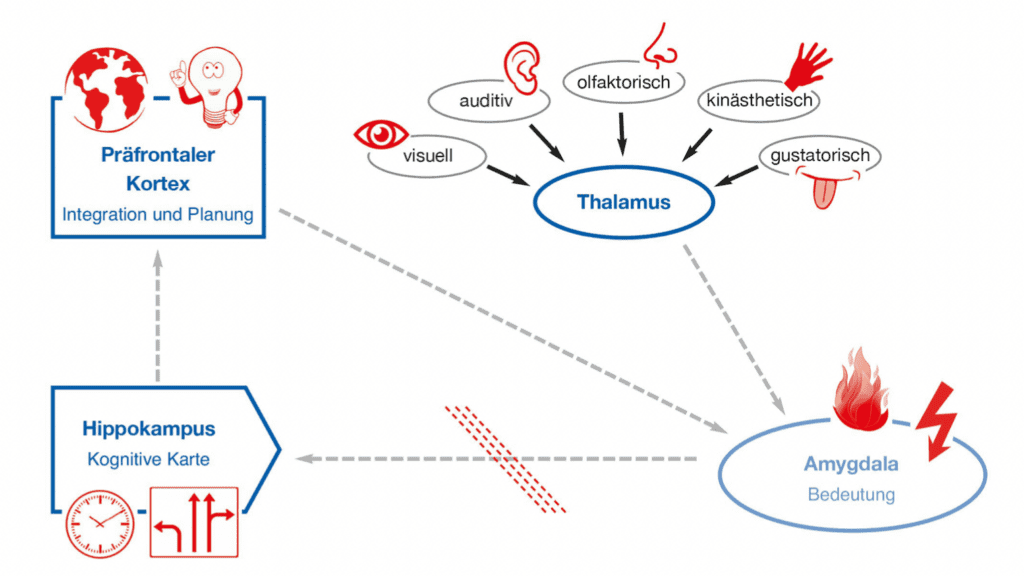

The intense fear felt in trauma can override all perceived internal and external images, sounds, smells and bodily sensations. Internal or external stimuli typically pass through a brain structure, the hypothalamus – the gateway to the brain – and are then first processed at a “primitive” level, in the so-called limbic system, where they are subjected to an initial evaluation: “good” or “bad”. The first reaction to the stimuli is corresponding: Curiosity or fear. The amygdala (almond nucleus) is the “fear centre” or the “alarm siren” of the brain. This primitive evaluation is inaccurate, often wrong, but unbeatably fast.

Further information processing only takes place later in higher structures. First, the hippocampus (seahorse) gives the event a temporal-spatial context, and finally, the information is presented to the brain cortex (the prefrontal cortex) for reconsideration. It connects the information with all our knowledge about the world and ourselves, with our previous experiences and solutions to problems. This processing gives rise to conscious mental images of precisely that inner and outer world in the situation in question, which is also stored as retrievable and structured memories.

When the amygdala is aroused by frightening input, the prefrontal cortex can recognize the context and develop rational coping strategies, through which the amygdala is then “shut down” or “cooled down” again, so to speak. Instead of general alarm, the previously frightening information is processed appropriately. Structured entries are made in the memory that records the experience. Such successful coping then strengthens us for future challenges. However, this requires a lot of energy and, above all, more time.

In extreme fear, e.g., in a traumatic situation, this standard information and integration process is blocked. The extreme over-excitation of the amygdala cuts the connection to the hippocampus. The stimuli associated with the traumatic situation, the images, sounds, smells, or bodily sensations, then remain “frozen” and unconnected at the primitive level of the amygdala. This is a kind of surge protection of the higher information processing in the brain. But powerlessness, helplessness, horror, disgust, or intense pain can also cause this blockade of information processing in the brain.

As a protection against overwhelming and threatening feelings and panic, the disturbed processing of stimuli and information results in an immediate childhood trauma reaction – the so-called dissociation: psychological functions that are usually connected fall apart, our perception, consciousness, thinking, acting and feeling become, partially or entirely, separated from each other. So that the mental assembling of situational stimuli into a comprehensible picture of the threatening situation is sabotaged, the colloquial language calls this state a “shock”. The result is the childhood trauma reaction of depersonalization, a form of dissociation. Self-perception shifts, and those affected feel alien in their own body, as if they are looking at themselves from the outside. They react entirely appropriate to their environment, but sensory perceptions such as pain or bodily feelings such as hunger and thirst may be disturbed. In derealization, a feeling of unreality sets in as a childhood trauma reaction. The environment seems strangely alien or somehow changed, less real and more like a film. (Read also the article on brain fog).

With the processing of stimuli in the developmentally old limbic system, the reactions to the trauma situation also turn out to be correspondingly primal; they are found in most of our animal ancestors – fight, flight, freeze and fawn, the Four F’s. They are the biologically anchored emergency response systems: Fawn (bonding system), Fight (attack) and Flight (leave the situation), and, if that doesn’t work, Freeze (play dead). The latter is the trauma-typical paralysis and numbing response.

Against this background, similar, non-threatening, everyday stimuli can later activate the amygdala and trigger strong fear reactions and other feelings – without the realization that the threat belongs “there and then” and that there is no acute danger at all in the “here and now. The trauma networks become active again in these trigger situations (flashback). The frozen ego state is “unfrozen” and builds up again in its awfulness.

Then those affected unexpectedly experience extreme fear or panic that has nothing to do with the actual situation. Most of the time, these fears are also experienced as alienating by themselves and their surroundings. Sadness or anger can also be triggered in this way.

Childhood trauma reactions: Nightmares, Flashbacks, Intrusions

“Natural” blockages of the information processing system, thus, lead to the typical post-traumatic stress symptoms. Even if trauma survivors feel as if they are losing their minds, these are normal reactions to an abnormal situation. Many people who have experienced a traumatic or frightening situation know some of these reactions: These are usually sudden, abrupt fears, images, or bodily feelings – triggered by some internal or external stimulus (trigger). Those affected are often unaware of the connection with the original situation, as the reactions occur at the “primitive” level of the amygdala.

- For example, a patient regularly feels nauseous when she goes to renovate her new flat. She cannot explain this to herself. Eventually, it turns out that her violent father had worked enthusiastically on beautifying her own flat and imposed himself on her to help renovate her first own flat, after she had moved out of her traumatic parental home.

- Another patient always experiences severe panic and fear of being run over when she wants to cross the road. Her disastrous expectation stems from her childhood, when her parents would take her sister somewhere and leave her alone without further justification. Then she was afraid that something terrible would happen.

- The same patient had an aversion to her reflection and photographs of herself – her parents had constantly lectured her about how clumsy, ugly and stupid she was.

Certain smells or body perceptions and even dreams can also be such triggers. The result is intrusions and nightmares. In these, traumatic situations with the associated, disconnected bodily state appear in the memory but are experienced as “dream-like”. On the other hand, the flashback is a hyperreal re-experiencing of traumatic situations. This is a difference similar to the one between experiencing a situation in the front row of a multiplex cinema and being present in the same situation.

Emotional flashbacks are a unique feature of cPTSD – they do not represent cinema-like experiences of a fragmented situation, rather they awaken the emotional parts of such situations: Helplessness, panic, anger, and sadness. Their overwhelming intensity is not to be explained by the trigger situation, but by experience. They can last minutes but also days, weeks, or months.

Childhood trauma reactions: Persistently heightened physiological arousal (hypervigilance)

As I said, a permanent fear of abandonment is the most terrifying thing that children in an abusive family can experience. This fear is so terrible that, on the one hand, it triggers the defensive reactions described above, so that, on the other hand, it is pushed out of consciousness. What remains is a permanently heightened arousal in the body, which can later lead to sleep disturbances, increased jumpiness or concentration problems.

- For example, one patient reports that he can hardly concentrate on reading the daily newspaper, or that when he reads a book, he suddenly forgets the content of the last pages.

- Another patient cannot remember what the doctor said to her when he told her the diagnosis. Instead, she remembers him wearing a yellow and blue tie and making a worried face.

In both situations, abandonment anxiety is reactivated, and, as a result, the amygdala becomes extremely over-excited. The prefrontal cortex is “switched off”, especially its left, more rational regions, including the language centre. Accordingly, facts are neither fully assimilated nor adequately linked.

Childhood trauma reactions: avoidance behaviour

By avoiding triggers, we can avoid being constantly “assaulted” by stressful emotions. This can be healthy. Avoidance becomes self-damaging when it leads to the suppression of specific topics (e.g., worries) and the avoidance of certain places (e.g., school buildings) or even objects (mirrors) and situations (photographs) – as in the example given above.

Childhood trauma reactions: trauma identity

The fragmented and de-contextualised information processing does not result in an inner image of the terrible situation, but in a trauma state (ego state associated with the trauma). It is based on neuronal networks that were activated in the situation, the trauma networks, which map a physical-bodily stimulus pattern. The ego state is “frozen” in the amygdala instead of being processed. The consequences of this childhood trauma response are described above.

The language areas of the cerebral cortex are other higher information processing stations. Their blockage prevents the linguistic and narrative sense-making and embedding of the terrible event, the mentalization. The social resonance system of the mirror neurons and the attachment system is also blocked, together with the meaning-giving processing of the situation.

In addition, children have no way of mentally classifying and understanding the abuse by parents, siblings, other close relatives or authority figures. They feel guilty about what happened and develop a negative self-image – the so-called trauma identity. It is characterized by several features that stem from one root – the fear of abandonment, which is a terrible experience for all mammalian babies, who need the mother’s comforting, reassuring, protective, holding and nurturing presence all the time in the beginning. Abandonment triggers a deep depression that truly cripples the ability to live, abandonment depression or the “Dark Night of the Soul”. It is so terrifying that several psychological protective mechanisms are brought into position against it like rings of fortress walls. These fortress walls lead to the characteristic behavioural patterns in cPTSD, the individual pattern of the Four F’s. Survivors of childhood trauma are actually constantly on alert, their thinking often trapped in catastrophizing expectations and black-and-white patterns. Their perfectionism and hard striving for achievement – to “magically” avert impending danger – are countered by pronounced fears of failure and feelings of inferiority. Successes are never earned, sure and lasting.

Moreover, the trauma identity is characterized by a lack of basic trust that the world is beautiful, life is worth living, and the child is lovable and unique. The result is toxic guilt and toxic shame, which call into question the very essence of the child’s and later adult’s being and profoundly damage their ability to attach and relate.

The trauma identity connects with the childhood trauma reactions mentioned above (hyperarousal, avoidance, flashbacks). As a result, attempts are made to cope with these experiences and behaviours, but they are often self-damaging. If they persist, there is often also a “repetition compulsion” that – seemingly incomprehensibly – reconstellates traumatizing relationship patterns, either only in specific situations or also in permanent relationships.

However, the fact that the trauma networks remain reactivatable also has its good side. With the resources of adult survivors, their activity in psychotherapy can be linked with new information and corrective experiences in such a way that emotional flashbacks are recognized less and less frequently and more quickly. Then, trauma survivors can also recognize and break through them in minutes. Moreover, there are learnable skills for dealing with self-harming coping strategies.

Sources:

Maercker, A.: Posttraumatische Belastungsstörungen.

Sack, M.: Schonende Traumatherapie: Ressourcenorientierte Behandlung von Traumafolgestörungen.

Walker, P.: Complex PTSD: From Surviving to Thriving: A Guide and Map for Recovering from Childhood Trauma.